Satellite Tracking Adult Male Green Turtles at the Archie Carr National Wildlife Refuge

By Dean Bagley, Research Associate,

University of Central Florida Marine Turtle Research Group

and Vice President, Inwater Research Group, Inc.

University of Central Florida Marine Turtle Research Group

and Vice President, Inwater Research Group, Inc.

My quest to learn about male turtles began with the late Boyd Lyon. Boyd came to study at the University of Central Florida in 2006 from NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, CA, where he worked with some of the best sea turtle scientists capturing turtles in the Galapagos, western Mexico, and San Diego, CA. He was experienced in capturing adult male turtles at sea, rodeo style, and planned to capture and study adult male green turtles off the Archie Carr National Wildlife Refuge (Archie Carr NWR). Tragically, he was lost at sea while perfecting his Florida technique, and for those of us who were left behind, the desire to find a way to honor his memory by continuing his work burned constantly. And then, one night, I found a male green turtle upside down in the surf, and two mating green turtle pairs a few kilometers away, and a new opportunity for studying adult male green turtles was born.

Most of what we know about adult Florida green turtles comes from what we’ve learned about females on the nesting beach, because they are readily available and easily approached for study. That leaves an entire segment of the population - the adult males - unstudied. Males leave the

Ms. Dean Bagley with a satellite-tagged female green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas). Photo: Jim Stevenson

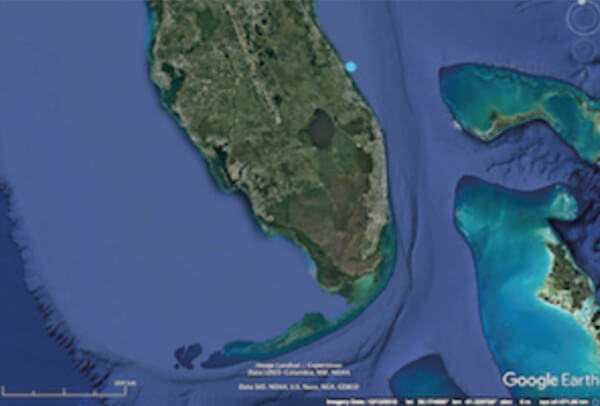

Ms. Dean Bagley with a satellite-tagged female green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas). Photo: Jim Stevenson Figure 1. Eight of nine males returned to different foraging areas in the Florida Keys, while one male returned to forage just 43 km south of his deployment location.

Figure 1. Eight of nine males returned to different foraging areas in the Florida Keys, while one male returned to forage just 43 km south of his deployment location.Nighttime beach surveys on ATVs are concentrated prior to or at the outset of the green turtle nesting season to encounter males upside down in the surf or on the beach (presumably dislodged from females by waves) or when they wash up on the beach as part of a mating pair. By encountering them at the nesting beach, we eliminate the expense and challenge of capturing them at sea. We also eliminate the need to conduct laparoscopy, an internal examination of gonads to determine if they are in breeding condition and will migrate. By attaching a GPS-enabled satellite transmitter at the nesting beach, we learn about their behaviors while in breeding mode, and about their migrations and destinations on the return trip at the end of the breeding season.

The University of Central Florida attachment crew make

The University of Central Florida attachment crew makesure Frank the green turtle is safely back at sea.

nesting beach as hatchlings, never to return to land. Since males are seldom seen, even the most basic biological information – like size and weight – is limited to those data obtained from stranded animals and rare inwater captures by researchers during the nesting season, with one exception. The Inwater Research Group has been capturing adult green turtles in an area west of the Marquesas since 2004, in what is still the only known adult green turtle foraging grounds in the continental U.S., slowly adding to the paucity of information on adult male green turtles. Because weather is hard to predict and at-sea conditions have to be just right for capture, the number of male green turtles captured remains low. Both the Inwater Research Group and this project are doing what we can to increase our knowledge and understanding of male green turtles.

The recovery of the Florida green turtle population ranks up there as one of the greatest conservation success stories of all time. Florida green turtle nesting in 1984 was at an all-time low with only 32 nests documented by the UCF Marine Turtle Research Group (UCFMTRG) in what is now the Archie Carr NWR, on the east central Florida coast. Fortunately, things have changed and green turtle nesting has been on the increase for years. Green turtles typically nest in a biennial pattern, so that every other year is a “high” nesting season (with a deviation from that pattern every now and then). In 2013, nest numbers at the Archie Carr NWR more than doubled from the previous high. In 2015, nest totals surpassed the 2013 totals, and we are anticipating that green turtle nesting in 2017 will once again set a new record. We saw mating pairs off the nesting beach occasionally in the earlier days but since the rapid increase of nest numbers, we are seeing mating pairs on a regular basis, especially in high nesting seasons.

This study aims to fill some of the data gaps regarding male green turtles. The Archie Carr NWR is a perfect place to conduct this research because this 21km (13 mile) beach accounts for about 32% of the green turtle nesting in Florida each year. The large number of females attracts the males, so that as nest numbers go up so do our encounters. We tracked two males in 2013, six males in 2015, one in 2016, and have five transmitters for deployment in 2017.

Encounters were so numerous that we could have tracked many more males if we’d had more transmitters. Our study provides information on body size, genetics, stable isotope signatures, when males begin to arrive off the nesting beach, how long they remain and where they spend their time, migratory pathways, foraging destinations, and home range once they return to those foraging grounds.

All nine satellite-tracked male green turtles from the Archie Carr NWR have returned to different foraging locations, and all but one to the Florida Keys between Biscayne Bay and Rebecca Shoals (Figure 1). One male returned to forage on the nearshore reef system in Indian River County, just 43 km south of his deployment location (Figure 3).

After three months we decided that this was his foraging area. Stable isotope analysis confirmed his signature to be very different than the other tracked animals, indicative that he foraged far removed from the others.

The first tracked turtle of 2017, “Frank”, was named for Frank Wojcik, the Founder and Director of the National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation

The first tracked turtle of 2017, “Frank”, was named for Frank Wojcik, the Founder and Director of the National Save The Sea Turtle FoundationWhile the sample size is still quite small – 9 males to date – these data provide the first look at what adult male green turtles in Florida are doing during breeding, migration and post-breeding foraging. They are providing insight on new foraging areas for adult Florida green turtles. These data were recently considered by Federal agencies in determining green turtle critical habitat. Using data generated by these transmitter turtles, we have identified foraging and sleeping areas that will be more closely examined during a Keys Megatransect. This vessel-based transect was begun in 2017 (but not completed) and will be conducted along Hawk Channel from Biscayne Bay to Rebecca Shoals to count adult green turtles and look for areas of high densities. We have five transmitters to deploy in 2017, which will increase our sample size by more than a third. Who knows what we might learn this year?

Our first transmitter turtle of 2017, “Frank”, was named for Frank Wojcik, the Founder and Director of the National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation and a supporter of our work. “Frank” was released just after sunrise at the Carr Refuge on the morning of 28 May 2017. He began moving south on the 29th, and continued that course until he reached Jupiter, Florida, at which point he moved offshore and began returning north. His movements are already very different from any of the previously tagged males. You can follow his movements online at www.seaturtle.org.

Helping Sea Turtles Survive for 39 Years

A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

State of Florida Registration Number CH-2841 | Internal Revenue Code 501 (c) (3)

Web Design & Development by Web Expressions, LLC