Can Marine Turtles Navigate? How Do We Know?

Mike Salmon, Professor

Department of Biological Sciences

Florida Atlantic University

Department of Biological Sciences

Florida Atlantic University

Some animals have an uncanny ability to complete long distance migrations, and in many species that task is done repeatedly during each individual’s lifetime. Migrators are organisms that specialize in finding habitats ideal for particular activities at particular times during their growth and development. For example, they may occupy habitats as juveniles (“nursery” or “developmental” habitats), different from those occupied by adults. They may also use specific habitats for breeding, for overwintering, or for finding food or shelter.

All species of marine turtles are superb migrators! In fact, they demonstrate this ability almost immediately as hatchlings that have completed embryonic development within an underground nest. Hatchlings then dig their way upward to the beach surface, scamper unerringly toward the surf zone, and swim vigorously offshore and out to sea. Thus begins a migration toward oceanic nursery areas hundreds of miles distant where they usually reside for many years.

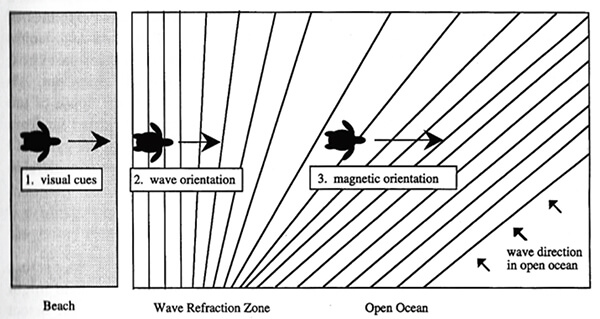

Figure 1. Offshore migration by hatchling sea turtles is accomplished by using three sets of cues in succession. After emerging from their nest, the turtles use visual cues to locate the surf zone, the motion of waves in shallow water to swim, and finally in deep water the earth’s magnetic field (where the waves no longer reliably indicate an offshore direction). (Modified from The Biology of Sea Turtles, Vol. I, CRC Press).

You might be curious about how a small turtle, minutes after it leaves an underground nest, can achieve a such a difficult task in a world it has never before experienced. Experiments done by inquisitive biologists have shown that the hatchlings accomplish this feat using three sets of cues, each of which keeps them on course during specific portions of their journey (Figure 1). While scampering down the beach, the turtles use visual cues; they crawl away from high structures (the dune and its vegetation toward land) and crawl toward lower vistas (the unobstructed view toward the sea). Once they enter the ocean, vision is switched

off and the turtles turn on a motion sensitivity that enables them to respond to the up-and-down displacements produced by oceanic waves where they swim: near the ocean surface. The turtles can actually use those displacements to determine the direction of the oncoming waves. They continue offshore by swimming in the opposite direction. This “wave compass” works because in shallow water, the waves are turned by bottom friction and always approach the shore parallel to the coastline (Figure 1). But later, in deeper water, wave direction is dictated by winds which can blow from other directions. Hatchlings “know” about how long their wave compass is reliable (~ 30 minutes) and so when that time ends, they switch to a third cue, the earth’s magnetic field, which dominates as a compass for the remainder of their migration. Magnetic cues also guide the migratory directions chosen by older turtles during their return from oceanic nursery sites to coastal habitats, where they finish growing. That return is characteristic of most species of marine turtles because food is more abundant near shore than in the open ocean, and more food results in faster, healthier growth.

Orientation biologists are fascinated by the precision and complexity of animal migratory movements as well as the variety of underlying mechanisms that enable the animals to complete these journeys. Here, I review their discoveries that explain how marine turtles migrate. In particular, I’ll emphasize the many experiments done by Professors Ken and Cathy Lohmann at the University of North Carolina, and by one of their doctoral students, Nathan Putman. It is largely through their efforts that we now understand how marine turtles became expert migrators, millions of years before we even thought about inventing the GPS!

After many years of study biologists realized that two processes, differing in complexity, appeared to control how all animals complete their migratory movements. One process is called orientation, or an ability to maintain a direction using an external cue, or guidepost, as a reference. Which cue is used varies with when and where the animal migrates; it can be astronomical in nature (the sun, stars, moon), an odor carried downstream by wind or water currents, a sound, the pull of gravity, the tides or, for sea turtles, even oceanic waves.

The offshore orientation of hatchlings, described above, took many experiments, done over several years, to fully understand and appreciate. How was it possible for most hatchlings to migrate successfully, given the variation in conditions they encounter in nature? For example, on some evenings hatchlings crawled from the nest to sea when the ocean was glassy calm. Yet, even in the absence of waves hatchlings still swam directly offshore in spite of other experiments showing that when waves were present, hatchlings used them as a guidepost.

The answer came from other experiments showing that the beach crawl could also be used to establish an offshore directional preference, transferred immediately in the absence of waves to the turtle’s magnetic compass. Similarly, if a female placed her nest too close to the surf zone, hatchlings experience an abbreviated crawl that was insufficient to establish an offshore directional preference. Under those conditions, swimming into oncoming waves served that purpose. Collectively, then, these experiments established that hatchlings possessed an amazingly effective set of flexible orientation mechanisms characterized by built-in redundant features. These virtually guarantee that under most circumstances, turtles successfully complete their offshore migration. It turns out that redundancy, the use of alternative mechanisms to orient migrations, is a general feature of these systems that applies to a wide variety of species, from birds to fishes and of course, to marine turtles!

But even an impressive system based exclusively on orientation pales in comparison with an ability to navigate. Navigation underlies some (but not all) migratory movements and is defined as an ability to reach a goal from any unfamiliar location. One can’t distinguish between orientation and navigation on the basis of how well animals maintain a direction; instead, homing experiments are done in which an animal is displaced to an unfamiliar location, released, and its ability to return observed (Figure 2). These tests show that orientation is a one-step process (a similar response to a guidepost) but navigation requires two steps. First, the animal must determine its location relative to a goal; this is known as the “map step”. Second, it uses that information to orient on an appropriate homeward path (the “compass step”; Figure 2). The guidepost(s) used for the second step are often identical to those used by animals only capable of orientation, but that’s where the similarities end. It’s the map sense that makes navigation such an interesting and more complicated process.

Think for a moment about what such a capacity means to a migrating animal! Maps only work if each location within the range of places an animal might frequent has a unique characteristic, one that defines and distinguishes it from any other location within that range. Humans create abstract maps of the entire world using a labelling system of orthogonal (fixed at a 90° to one another) bi-coordinates we call latitude and longitude. Animal maps must also consist of bi-coordinates though they do not necessarily have to be

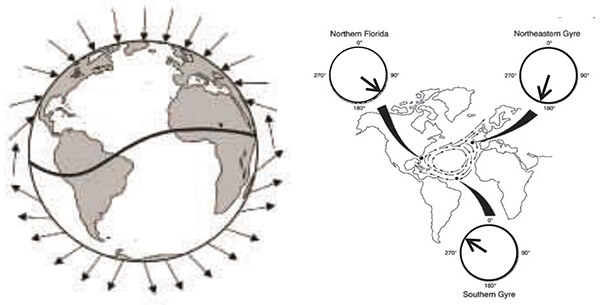

Figure 3. Left: The earth’s magnetic field consists of lines of force (small arrows) that produce a symmetric array of gradually changing dip angles. These range between 0° (lines parallel to the earth’s surface) at the magnetic equator that gradually increase to 90° at the magnetic poles. An animal that can detect dip angle can use that information to determine its North-South (N-S), or latitudinal, location on the earth’s surface. Magnetic field strength also varies along a N-S axis. It is weakest at the magnetic equator and strongest at the magnetic poles. Right: Hatchling loggerheads orient in different directions (see circle diagrams) when exposed in the laboratory to the magnetic field present on the west, northeast, and south side of the circular current (the North Atlantic Gyre) that is their nursery. Since their orientation varies with N-S location, the turtles must be able to determine their latitude. That determination can be based upon magnetic field dip angle, magnetic field intensity, or both qualities. However, their ability to determine their longitudinal (E-W) position is not conclusively proven by these observations. (Modified from Lohmann Lab. Webpage, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.).

arranged orthogonally. Ken and Cathy Lohmann showed that hatchling loggerhead turtles used the earth’s magnetic field as a kind of map to maintain their position within the North Atlantic Gyre current, their nursery area (Figure 3). This ability was evident in turtles captured immediately after they left the nest but before they crawled down the beach to the ocean. Thus, the hatchling map enabled the turtles to orient appropriately in an environment that they had yet to experience!

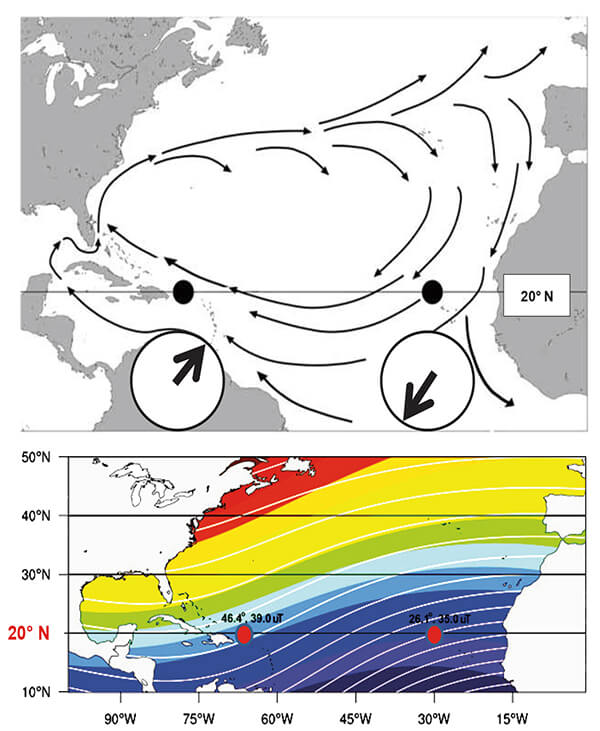

Figure 4. This experiment shows that hatchling loggerheads can use the earth’s magnetic field to determine their East-West (longitudinal) position. Upper diagram: Loggerhead hatchlings are divided into two groups. One group is exposed to a magnetic field on the east side of the Atlantic Ocean while a second group is exposed to a magnetic field on the west side. Both fields occur in the North Atlantic Gyre nursery area, and both are centered at the same (20° N) latitude. The hatchlings in each group orient in opposite directions (circle diagrams below the gyre), and so distinguish between the two locations. Lower diagram: Colored layers represent the gradient in dip-angle while the white lines represent the gradient in magnetic intensity. Both increase to the north but in patterns that differ so that each location has unique values of dip angle (here, 46.4° vs. 26.1°) and magnetic intensity (39 nT vs. 35 nT [= nanotesla]). These results show that the turtles distinguish between those values to determine their longitudinal position. (Modified from N. Putman et al., Current Biology, Vol 21, pp. 463-466, 2011).

Perhaps most interesting of all, the Lohmanns also showed that the hatchling map used two features of the earth’s magnetic field: its dip angle (the angle between the field lines and the earth’s surface) and field intensity, or strength. Dip angle varies from 0° (parallel to the earth’s surface) at the magnetic equator to 90° at the magnetic poles (Figure 3, left). Intensity showed a similar arrangement of values, from weakest at the magnetic equator to strongest at the magnetic poles. But bi-coordinates can only act as labels if their signatures at each location differ. Dip angle and intensity do vary at different locations but those differences are large only along a north-south (N-S), or latitudinal axis. Those observations led to the conclusion that hatchlings could use magnetic cues to determine their latitude (Figure 3, right), but were incapable of responding to the much smaller magnetic differences along an east-west (E-W), or longitudinal axis. If that was true, then marine turtles could not complete the map step from a location to the east or west of a goal. Was that actually true?

To find out, Nathan Putman challenged loggerhead hatchlings to distinguish between two locations within their migratory range, one on the east and the other on the west side of the North Atlantic gyre current (Figure 4). Those locations were at the same (20° N) latitude but at a different longitude. The turtles easily made that discrimination; in fact, at each site they oriented in the opposite direction (Figure 4). No question, then, that the turtles were capable of distinguishing between the much smaller differences in dip angle and intensity along an E- W axis using magnetic cues. The inescapable conclusion: even as hatchlings, marine turtles can navigate! Amazing stuff!

And so what we’ve learned, over almost 30 years of study, is that marine turtles complete their migrations using sophisticated systems of orientation and navigation, with orientation playing a dominant role during the initial phase of migration and navigation being used during the later stages. Both systems are apparently innate and show little, if any, evidence that experience (in the form of learning) has much of an influence on how they work. At the same time, we know that the earth’s magnetic field changes through time. Those changes require that human mariners adjust their compasses every year or two. Turtles must also make adjustments, perhaps during their migrations between feeding and breeding habitats, and certainly as different generations over their long evolutionary history. After all, marine turtles have been migrating across ocean basins for over 100 million years. That history shaped their already remarkable ability to locate distant goals, hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

Helping Sea Turtles Survive for 39 Years

A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

State of Florida Registration Number CH-2841 | Internal Revenue Code 501 (c) (3)

Web Design & Development by Web Expressions, LLC