2020 Florida Hawksbill Project

Even though 2020 turned out to be a big challenge in many ways, the Florida Hawksbill Project still managed to reach some important milestones. It’s a little hard to believe, but the Project is now going into its 17th year! As a quick recap, the Florida Hawksbill Project’s mission is to describe in detail the abundance, distribution, and ecology of hawksbill turtles in Florida waters. Over the years, we have explored the genetic origins, movements, gender ratio, health, and diet of these beautiful turtles from the offshore reefs of Jupiter all the way to Key West.

The most significant thing that has come from our work so far is that we’ve determined that rather than being a permanent home, Florida is a ‘stop along the way’ for hawksbills that had hatched elsewhere in the Caribbean, mostly the beaches of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. After leaving their nests, they spent some time floating in the Gulf of Mexico before returning to the Caribbean via the straights of Florida. The semi-random dispersal of these young turtles lead some of them to take up residence in the Florida Keys,

The particular configuration of this ‘natural laboratory’ permits us to explore a number of fascinating aspects of the biology of hawksbills as they negotiate through these formative stages of life.

We are nearing the completion of several interesting studies that have been in the works for some time. As someone who has worked in sea turtle rehabilitation, I appreciate the value of having reference material on hand when evauating a new ‘patient’. Blood is routinely extracted and analyzed, resulting in data that guide treatment plans. Though data were available for other sea turtle species, I realized that there were no clinically-useful reference intervals from which hawksbill blood parameters could be directly compared, so I teamed up with Dr. Nicole Stacy from the University of Florida to start collecting blood samples from the turtles I encountered during our field surveys. After three years of collecting, our team just met our goal of 70 samples, allowing us to move forward with the analysis and publication of the results. We’ve welcomed Dr. Justin Perrault of the Loggerhead Marinelife Center to our team as our expert statistician, and we’re looking forward to publishing what will be by far the most comprehensive evaluation of hawksbill health and physiology yet available.

which happens to be the southern end of the SE Florida Continental Reef Tract that hugs Florida’s SE coast all the way up through Palm Beach County. This long line of reefs will become home to these little turtles for the next 15-20 years or so before they reach maturity themselves, and hear the call to return to their origins of birth to continue the cycle. Once they’ve gone, it seems Florida is ‘old news’, and we’ll very likely never see those turtles again in Florida waters.

Florida’s hawksbills, from what we’ve seen so far, are considered ‘specialists’ in their approach to life; they pretty much stick closely to specific coral reef neighborhoods where they consume a narrow selection of sea sponges. The Florida Keys provide ample shallow reefs for newly arrived juveniles, and as they grow, they become more able to fend for themselves on deeper reefs that are more prevalent in the northern part of the reef tract. As they broaden their habitat choices, they encounter new food choices, predators, and competitors.

While the turtles were in-hand, we also collected small samples of their shell and skin to help us reveal their dispersal patterns after they had arrived in Florida’s waters. Since the old adage “you are what you eat” actually rings true, we are able to use unique signatures of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur that accumulate in their tissues to trace their activities for up to 10 years prior to sample collection. Since the outer layers of the turtles’ shells grow very slowly, just like our hair and fingerhails, we are able to look back in time to explore subtle dietary changes that the turtle may have experienced over time. Some of these shifts may represent shifts in foraging location, which will be revealed in the corresponding site-specific combinations of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur signatures we discover in their tissues. Although there have been some coronavirus-related delays, the samples are on-deck for analysis by our colleagues Dr. Simona Ceriani and Sue Murasko at the Florida Marine Research Institute, so results are soon on the way

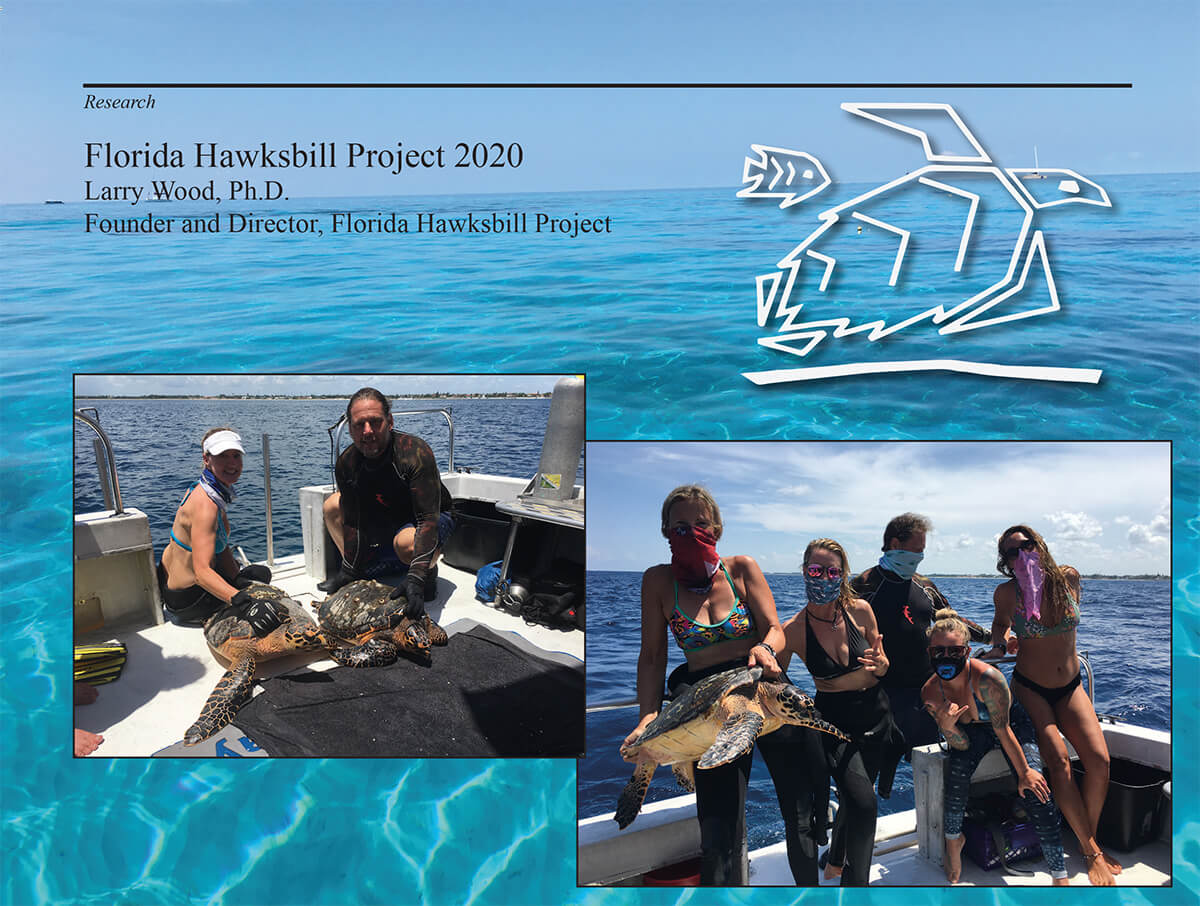

Meanwhile, the core effort to document the abundance and distribution of hawksbills continues. We isolated ourselves as much as possible from unintended exposure to covid-19 on our field days by chartering a dive boat exclusively for the team. Our long-time friend Captain Sandy Brammier from Ocean Quest Scuba provided expert transport for us, and inspired us to re-visit reef sites in Palm Beach that we hadn’t surveyed in a number of years. Not only did we find plenty of new turtles to add to our study, we also encountered individuals we had tagged before, including some from five, nine and even twelve years ago, still hanging around the same places we’d found them the first time around.

Though we could only get there once this year, our team also had a very productive weekend in Key West. We happened across stellar water conditions for snorkel surveys, and were able to capture several little hawksbills, including a captive-reared one we had released there in 2019. As I mentioned before, many of Mexico’s young hawksbills float around in the Gulf prior to reaching Florida. Unfortunately, some wash ashore on Texas beaches, usually after hurricanes. The National Marine Fisheries Service helps operate an aquarium and research center in Galveston that specializes in sea turtle rehabilitation, so they care for all the small hawksbills that wash ashore each season. Once recovered and fostered for about a year, they are usually of the size that they would be otherwise transitioning to coral reefs for food and shelter, so they are best released in places we know this process to occur, for example, Key West. This particular little fellow showed the resilience of sea turtles by not only surviving, but matching the impressive growth rates of its wild counterparts after arriving from a captive setting.

All totaled, we captured 19 ‘new’ turtles and recaptured 7 ‘known’ turtles this year, which is really great considering the restrictions we were facing. We’re now up to a grand total of 264 turtles captured, and as a matter of coincidence, we captured the 250th turtle on the 1000th survey of the Project this July. I’d like to give my heartfelt thanks to our fantastic team of volunteer divers and snorkelers, and the National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation for financial and logistical support. I’m excited to see what the new decade will bring!

**All activities authorized by State and Federal Research Permits

Helping Sea Turtles Survive for 39 Years

A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

State of Florida Registration Number CH-2841 | Internal Revenue Code 501 (c) (3)

Web Design & Development by Web Expressions, LLC