Too Much of a Good Thing: Sargassum Blooms and Hatchling Production at a Local Nesting Beach

Mike Salmon, Research Professor, Florida Atlantic University

We are living in the Anthropocene age, in which human influence on the planet is so profound – and terrifying – it will leave its legacy for millennia. (Robert Macfarlane, The Guardian)

It’s been known for many years that after Florida’s loggerhead and green turtle hatchlings crawl down the beach from their nest and enter the sea, they head for the Gulf Stream current where they find food and shelter in floating mats of an algae, known as Sargassum. These mats were first described by Christopher Columbus and his sailors in 1492, which reminded them of “salgazo,” small grapes in Portugal, and thus the name of the central gyre of the North Atlantic became the Sargasso Sea. However, until recently little was known about how these two species exploited this crucial “nursery”, and not surprisingly it turns out that they do so differently.

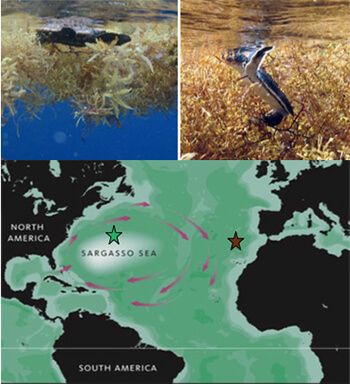

Loggerhead hatchlings are generally dark brown in color, with a carapace (top shell) that in texture resembles an irregular clump of the algae. They generally crawl on top of the mat or float adjacent to it, and only move sporadically when food drifts close by (Figure 1). For that reason, they are known at this stage of their development as “sit-and-wait” predators. In comparison, green turtle hatchlings have a dark black carapace that contrasts in color with the browns of the algae. They hide in the mat by burrowing into it, with only their head protruding (1). They are also much more active than loggerheads. Until recently, they were rarely seen in the mats. That’s because when approached by either a predator or a boat with curious scientists on board, they avoid detection by diving under the Sargassum mat and swimming rapidly away.

Another difference between the species is how Sargassum mats are exploited. Recent collaborative studies done by three Florida scientists (Kate Mansfield, Jiangang Luo and Jeanette Wyneken) revealed that most juvenile loggerhead remained associated with mats in the Gulf Stream, riding that current across to the eastern Atlantic (Figure 1). However, most juvenile green turtles of similar age leave the Gulf Stream and swim into the Sargasso Sea. Thus, green turtles differed from loggerheads geographically in where they spend their “lost years”. All of this information is vitally important since “... studies in which we learn where little sea turtles go to start growing up are fundamental to sound sea turtle conservation. If we don’t know where they are and what parts of the ocean are important to them, we are doing conservation blindfolded” (J. Wyneken).

Figure 1. Upper left, loggerhead hatchlings rests above a Sargassum mat. Upper right, green turtle hatchlings rest within the mat with their head protruding to watch for approaching threats. Bottom: The Gulf Stream gyre encircles the Sargasso Sea. Loggerheads ride the gyre to nursery habitats on the east side of the Atlantic (brown star) while green turtles leave the gyre and reside in the Sea itself (green star).

Too Much of a Good Thing

Historically, Sargassum rafts in the ocean have consisted of numerous long, narrow and shallow rafts, scattered like wisps hundreds of meters apart over the sea surface. That situation was promoted by the low concentration of nutrients in the Sargasso Sea, considered by oceanographers as a biological “desert”. But since the 1980’s, disturbing increases have occurred in the abundance and distribution of the algae in the Western North Atlantic and Caribbean Sea. These algal rafts have taken the form of massive “blooms”, or increases in the density and extent of the mats in the Caribbean and the open ocean, and in the major oceanic current systems in the Atlantic such as the Loop Current in the Gulf of Mexico, and the Gulf Stream (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A huge raft of Sargassum, floating in the open ocean.

The factor or factors involved in promoting these changes were unknown early on, but became apparent after marine ecologists began making key measurements. The culprits are geographically widespread and multiple (reviewed in 2): (i) forest clearing for agriculture in the Amazon, (ii) runoff of high concentrations of the nitrogen and phosphorus from those soils used to fertilize crops into the Amazon, Congo, and Mississippi rivers, and (iii) inputs of nutrient “dust” from Saharan African farming, carried by trade winds, and dropped into the western Atlantic and Caribbean seas.

Those of us living in South Florida find these stories of nitrification painfully familiar! The addition of nutrients that enhance plant growth come from farms, groves, lawns, leaky septic tanks and golf courses. They wash into Lake Okeechobee and drain into the Everglades, and are also released into the Caloosahatchee and/or St. Lucie Rivers. This release of nutrient-rich waters results in algae blooms, hypoxic waters, and toxic conditions that lead to die-offs of fishes and other aquatic wildlife.

Figure 3. Left: Sargassum accumulates on the beach, just above the surf zone where it might act as an obstruction that prevents hatchlings from entering the sea. Right: Josh measures some algae that has accumulated in the surf zone.

Figure 4. Loggerhead hatchlings crawling from the nest to the sea at a Boca Raton nesting beach.

The results revealed that those accumulations posed a real threat (3). Over 43 evenings when Josh measured responses to “natural” accumulations, there was a 22 % reduction in the number of hatchlings that could negotiate the barrier and swim offshore. The result: of the 12,730 hatchlings produced by that year, only an estimated 9,930 made it to the ocean.

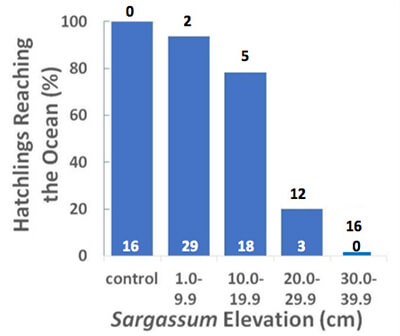

Figure 5. Results of an experiment to determine whether hatchlings can climb over Sargassum mats varying in elevation. Controls are tested in the absence of algae; all 16 crawl to the sea (lower numbers). As algal elevations increase, that proportion declines while those that fail increases (upper numbers). Finally, at elevations exceeding 30 cm, no turtles enter the sea.

When manipulating algae elevation, he found that barriers exceeding 20 cm in height (almost 8 inches) significantly reduced the ability of the turtles to reach the ocean, and those exceeding 30 cm in elevation (12 inches) were a complete barrier (Figure 5).

Impact on Marine Turtle Nesting Beaches

Joshua Schiariti entered the Masters of Science program in biology at Florida Atlantic University with interests in animal behavior, and since that’s my field he became my student. We both were impressed by the obvious accumulation of Sargassum, both in the shallow surf zone and on the nesting beach at Boca Raton (Figure 3). Could those accumulations act as a barrier to a small turtle, crawling from the nest to the sea (Figure 4)? If so, then the algae might indeed represent a significant threat, one that reduced nesting beach “productivity” in a species whose numbers had already been negatively affected by human activity. If those populations are to recover, they must produce adequate numbers of hatchlings!

To find out, Josh designed two kinds of experiments, each requiring that he determine how well loggerhead hatchlings negotiated the algal accumulations over the course of a nesting season. To find out, we obtained a state permit to obtain the turtles from nests in the afternoon of the evening when they would normally emerge. After dark, these turtles were released on the beach where they crawled into the mats. After observing their behavior, they were recaptured and released to begin their offshore migration.

In one set of experiments, Josh measured the elevation of the algal mass left “naturally” on the beach each evening. Those tests allowed him to estimate how many turtles could crawl over, around or through accumulations that varied in density and elevation from one night to the next. In the second set of experiments, Josh released hatchling on the beach near to algal accumulations that he created, and that varied systematically in elevation. That enabled him to more precisely determine the probability that hatchlings encountering an algal barrier of specific elevation could cross it to reach the sea.

When they encountered an algal mass, hatchlings either crawled along the edge until they became exhausted, reversed direction and crawled away from the sea, or fell backward after attempting to climb over the mass (Figure 6). Those that explored the barrier either managed to find a spot where they could climb over the algae, or crawled along the edge of the mass until they found an opening leading to the sea. But even when hatchlings successfully negotiated the algae mass, the time spent on land was increased. In a previous study, those delays in seafinding were shown to increase the probability that the turtle would be detected, and taken by, a terrestrial predator (4).

Conclusions

There are presently ~ 8 billion humans on this planet. Ultimately, it is the expansion of the human population that serves as the impetus for most agricultural activity, coupled with the need for improved yields that drives the use of fertilizers that are now impacting oceanic ecosystems in increasingly negative ways. We in Florida are well aware of these relationships. Red tides, a bloom of a single-celled and highly toxic algal organism, were known to occur on rare occasions historically and in restricted locations in Florida waters. Today, these blooms are increasing in frequency, duration, severity and geographic extent. They are also strongly associated with nutrient influxes into coastal waters where they have devastating effects on fishes, turtles, manatees and marine invertebrates.

Figure 6. Night-time photos show what happens to crawling hatchlings when they encounter the algae mat. Black arrow points toward the sea; white arrow show the turtle crawl direction. Upper left: a hatchling crawls parallel to the mat edge. If it finds an opening, it may reach the sea. Upper right: a turtle crawls over the mat to reach the sea. Lower left: a hatchlings falls backward landing upside-down after failing to scale the mat. Lower right: the turtle reverses direction and crawls away from the sea.

It thus should come as no surprise that Sargassum, so essential as a nursery habitat for hatchling and juvenile turtles, has become “too much of a good thing”, and in the process may actually represent a threat to the recovery of these endangered and/or threatened species. Its blooms represent a symptom of how we are increasingly upsetting balances in natural ecosystems, and in the process causing immense harm to the planet and its inhabitants. Hopefully, we’ll soon reverse those trends, learn how to correct our behavior, and live more harmoniously with Mother Nature!

Further Reading

(1) Smith, MM. & Salmon, M. A comparison between the habitat choices made by hatchling and juvenile green turtles (Chelonia mydas) and loggerheads (Caretta caretta). Marine Turtle Newsletter 126:9-13, 2009.

(2) Lapointe, BE et al. 2021. Nutrient content and stoichiometry of pelagic Sargassum reflects increasing nitrogen availability in the Atlantic Basin. Nature Communications 12:3060, 1–10.

(3) Schiariti, JP & Salmon M. 2022. Impact of Sargassum accumulations on loggerhead (Caretta caretta) hatchling recruitment in Southeast Florida, United States. Journal of Coastal Research (in press; DOI: 10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-21-00134.1.)

(4) Erb, V & Wyneken J. 2019. Nest-to-surf mortality of loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) hatchlings on Florida’s east coast. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6, 271. Doi:10.3389/fmars.2019. 00271.

Helping Sea Turtles Survive for 39 Years

A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

State of Florida Registration Number CH-2841 | Internal Revenue Code 501 (c) (3)

Web Design & Development by Web Expressions, LLC