Rescued Turtle on the Road to Recovery at Gumbo Limbo

Jake Lasala, Doctoral Candidate

Department of Biological Sciences

Florida Atlantic University

Department of Biological Sciences

Florida Atlantic University

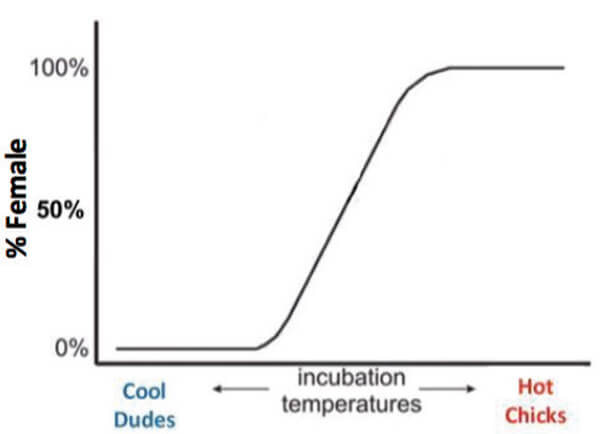

In a previous issue of “Outreach,” Boris Tezak and Itzel Romero described their new methods for identifying the sex of hatchling sea turtles and discussed how sex determination in mammals and birds differs from that of marine turtles. Sex determination in mammals and birds is controlled by sex chromosomes; in marine turtles (and many other reptiles), environmental factors determine the sex that embryos in the nest develop. Specifically, warmer temperatures in the middle third of incubation produce more females and cooler temperatures produce more males (Figure 1.). Other environmental factors affecting sex ratios produced in each nest include rainfall, sand moisture and shading. What this means is that as the earth continues to warm, we can expect to see more female and fewer male hatchlings. This outcome is especially important in Florida where, at the present time, estimates are that over 90% of loggerhead sea turtle hatchlings are female! As Florida beaches produce several million hatchlings per year, it is likely that the adult sex ratios in this population will become increasingly skewed toward females.

You may be wondering why this might be a problem? After all, wouldn’t more females = a larger breeding population = more turtles?!

Figure 1: Theorized sex ratio curve based off of nest incubation temperatures. Warmer temperatures produce more females (“hot chicks”) and colder temperatures produce more males (“cool dudes”). Intermediate temperatures produce a mixture of male and female hatchlings.

But the situation isn’t that simple. As the proportion of females increases, their choice of mates can be expected to dwindle, and this is not a positive outcome. Marine turtles display sexual reproduction, in which both males and females “scramble” their genes to produce offspring that not only differ genetically from each parent, but also from their siblings (brothers and sisters). This offspring genetic variation is essential for coping with an uncertain world as it increases the chances that at least some young, by chance alone, will be able to withstand future stresses associated with changes in their food supply, competition from other organisms, disease-producing microbes, predators, and other threats (including climate change). If the proportion of males in relation to the proportion of females is reduced, the result is a loss of genetic variation that the males contribute to offspring. When genetic variation is thus reduced, so is the probability of offspring survival. It is therefore reasonable to speculate that the increasing temperatures in Florida could further alter marine turtle sex ratios to the point where adults in “male-deficient” populations would be unable to produce enough competent offspring to replace themselves, with the eventual result that the turtles might go extinct.

Have I gotten your attention?! I hope so!! New methods to identify hatchling sex ratios (described by Tezak and Romero) reveal how environmental change alters hatchling sex ratios, but that knowledge is only half of the equation. My research focuses on the other side of the sex ratio question: what is happening at the level of the adult breeding population? Specifically, I look at the present-day composition of breeding adult populations to estimate the proportion of males to females.

Some organisms are challenging to study because their habitat is not readily accessible. In some extreme examples, one sex is readily observable but the other sex remains cryptic; this is especially true for marine turtles. The most significant events in the life of a marine turtle take place at sea and can’t be directly observed (e.g. mating, Figure 2). In Florida, it is easy to walk the beach on a summer night and find a nesting female. They can also be tagged and counted by observers.

Figure 2: Two green turtles mating in-water. Image taken by Guinjata Dive Center.

Males, though, typically stay in the ocean where they can’t be seen. One might assess population health and estimate adult sex ratio by taking a boat into open water to count all the turtles you encounter. However, this census method is very expensive and fails to detect all the individuals in a population. Also, even if these problems could be overcome, one couldn’t be sure that every male is competitive and is able to contribute his genes to the next generation. Much depends on whether a female finds him attractive.

Thus, in reality, in marine turtle populations with skewed sex ratios, I seek to answer two questions: (i) how many males are “out there”, and (ii) how many of those males routinely mate with each female? If, from the genetics of the hatchlings produced in each nest, I can identify the males as individuals, I can answer both questions simultaneously.

Our lab is developing new techniques to understand the process of environmental sex determination, and to estimate current hatchling sex ratios on our beaches. However, because marine turtles can take 20 – 30 years to reach sexual maturity, these new techniques provide us with little understanding of the sex ratios in the adult population. In-water counts indicate that there are more sexually mature females than males; we might expect this outcome if hatchling sex ratios 20 – 30 years ago were also biased toward females. However these numbers are obtained, they are always a proportion, rather than the entirety, of the breeding population. Females, for example, do not breed every year; they require a few years of feeding to accumulate the energy used to produce the hundreds of eggs they place in nests during a single breeding year.

Mature males, however, may breed more frequently since the energetic demands involved in searching for mates (and competing with other males for mating opportunities) may not be as great. Thus, what’s really important to determine is the operational sex ratio, or the ratio of breeding males to breeding females during any one breeding season. My research project is designed to address this question by identifying parentage.

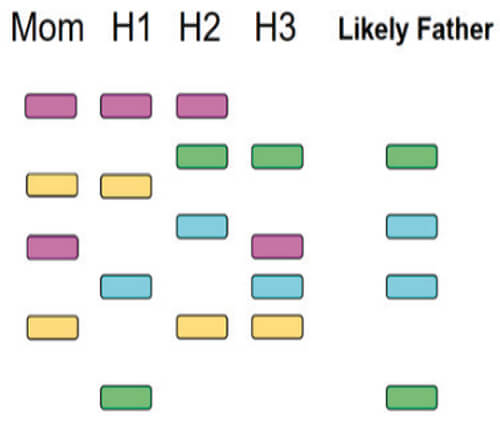

I can identify how many males a female has mated with by using genetic markers, or “fingerprints,” from small samples of blood or skin. I use tissue samples from females to identify maternal genes, and tissue samples from hatchlings to identify their genes. Half of each hatchling’s genes are maternal; half are paternal. For each hatchling, I identify maternal genes by matching their characteristics (how they migrate on the surface of a charged gel) with those of the mother; any genes that don’t match are paternal (Figure 3). The final step in this molecular detective work is to compare the characteristics of the paternal genes in tissue samples taken from hatchlings in a single female’s nest. The number of different paternal genes in a nest equals the number of males mating with the female laying the eggs placed in that nest.

Figure 3: Illustrative gel showing how paternity is analyzed from the genetics of the female (“Mom”) and three of her hatchling offspring (H1, H2 and H3). The female has two copies of the pink and orange gene. The hatchlings receive one copy of each gene from Mom. Any other genes that the hatchlings’ possess (green,blue) must have come from “Dad”. Thus, in this example,the female mated with only one male. My data indicate that in sea turtles, that’s rare, as most of my females mated with more than one male.

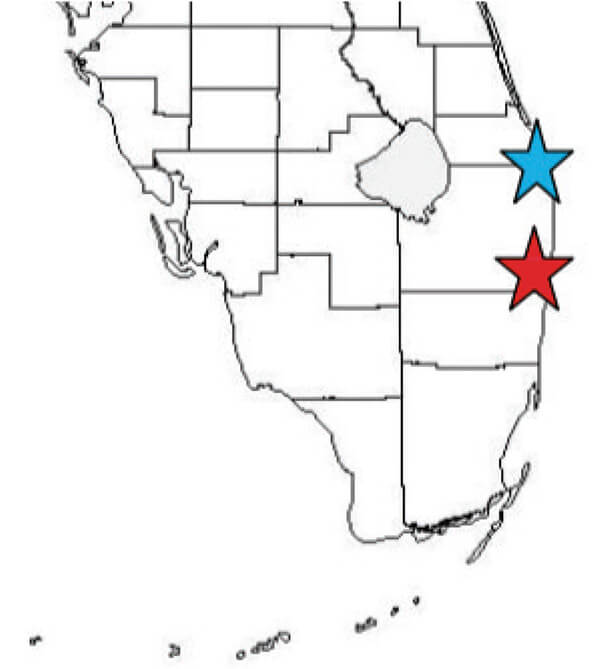

Figure 4: My study sites (Blue star, Juno Beach; Red star, Boca Raton) in Palm Beach County, Florida, where I was assisted by the marine turtle program at the Loggerhead Marinelife Center and the Gumbo Limbo Nature Complex, respectively.

I’ve collected tissue samples from loggerhead, leatherback and green turtles nesting on two different beaches in Palm Beach County (Figure 4). These beaches were selected because of their profound differences in nesting density: Juno Beach appears to be a preferred nesting site for all three species. If these two locations are within the same nesting/breeding assemblage, I would expect to see similar behavior (e.g. similar successful mating attempts).

What we found was impressive. From 2013-2015 I determined that all three species do mate with multiple males (Loggerheads > Greens > Leatherbacks; Table 1). However, I never found a male that mated more than once. I hypothesize that either a) there are more males mating than expected, or b) females encounter unique assemblages of males as they migrate from different locations toward the nesting beach. In reality, the number of males I documented for loggerheads (~29,000) is a relatively small proportion compared to the number of females nesting in Florida (~ 200,000 turtles).

We also determined that females nesting at Boca Raton on average mated with fewer males than females at Juno Beach. Why that happens remains an interesting, but presently explained, result.

My next goal is to analyze data from 2016 which include repeat nests from the same female. Those results should indicate whether females only mate before they start nesting, or if they continue to select mates while they nest and in the process, produce hatchlings with different fathers as the breeding season progresses.

To properly plan current and future conservation efforts it is essential that baseline census estimates be quantified and robust. That’s why the information I’ve obtained is so important. It’s encouraging that the nesting populations of marine turtles in Florida are increasing. However, while this finding is positive we have no idea whether the population of males is also keeping pace. If, as our data on hatchling sex ratios suggests, the number of males being produced is in decline then so, also, should be operational sex ratios in future studies done much like mine. Those observations will be an early warning signal that the quality of future hatchlings may not match the quality of present-day hatchlings, and that a dramatic shift in population size and health may be just around the corner.

This research was partially supported by The National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation’s Scholarship Program.

Species and Study Site

Mean Number of Fathers per Nest (A)

Mean Number of Nesting Females (B)

Estimated Number of Males (A x B)

Loggerheads

Juno Beach

Boca Raton

Juno Beach

Boca Raton

5.1

4.2

5,717

487

29,161

2,045

Greens

Juno Beach

Boca Raton

Juno Beach

Boca Raton

2.7

1.4

3,432

220

9,266

308

Leatherbacks

Juno Beach

Boca Raton

Juno Beach

Boca Raton

1.6

1.2

121

11

193

13

Table 1: Method for estimating the number of males breeding at my study sites. I used data from the gels (Figure 3) to determine how many males, on average, contributed genes to the hatchlings emerging from each sampled nest (Column A). I used known information about how many nests each female places on a beach during a given breeding season to estimate the size of the female population (Column B). The estimated number of males is then A x B, assuming each female mated with a different subset of males. That assumption was confirmed at my study sites.

Helping Sea Turtles Survive for 39 Years

A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

State of Florida Registration Number CH-2841 | Internal Revenue Code 501 (c) (3)

Web Design & Development by Web Expressions, LLC