A New Approach to Identifying Sex in Hatchling Turtles, and a Potential Game-Changer for Assessing Marine Turtle Hatchling Sex Ratios

Boris Tezak, Doctoral Candidate

Biological Sciences

Florida Atlantic University

Biological Sciences

Florida Atlantic University

One of the most fascinating features of sea turtle biology is that these animals do not have sex chromosomes, nor do they produce an almost identical ratio of boys to girls (as do we and many other animals); instead, they display a mechanism known as temperature dependent sex determination (or TSD) and an unbalanced sex ratio that normally favors females. TSD means that the temperature of the sand surrounding the eggs during incubation determines whether the embryos will develop into a male or female (Figure 1). Although how this works is still unresolved, we know that warm temperatures produce females and cool temperatures produce males (think hot chicks and cool dudes!).

Lab experiments over the past two decades show that under constant incubation conditions, temperatures below 27° C (80.6° F) produce all-male hatchlings, temperatures above 31° C (87.8° F) produce all female hatchlings,

Figure 2. Laboratory based sex ratio-temperature response curve for loggerhead turtles. The graph shows the relationship between temperature and the resulting sex ratios they produce in sea turtle nests. At low temperatures, all of the hatchlings are male; at high temperatures, all are female. At intermediate temperatures, the ratio of males to females varies and is 50:50 at 29° Centigrade, the “pivotal” temperature (PT).

Figure 1. Temperature dependent sex determination (TSD) in sea turtles. Cool temperature promote the development of males; warm temperatures promote the development of females.

and tmperatures in between produce a mixture of male and female hatchlings from that nest (Figure 2). This means that one of the most important aspects of sea turtle biology (their sex!) is dangerously vulnerable to changes in climate. Recent studies have highlighted that with increasing temperature, the sex ratios of sea turtle populations could gradually become even more, and dangerously, biased towards females. However, determining whether this prospect will happen is difficult to assess for two reasons. First, it takes marine turtles ~ 25 years (a bit sooner in some species; a bit later in others) to reach sexual maturity, so estimating sex ratio shifts in the population can’t be done immediately. A second problem is that there is no convenient way to estimate how many male and female turtles are being produced at the major nesting beaches across the globe because neither the hatchlings nor the juveniles differ in appearance until they reach sexual maturity.

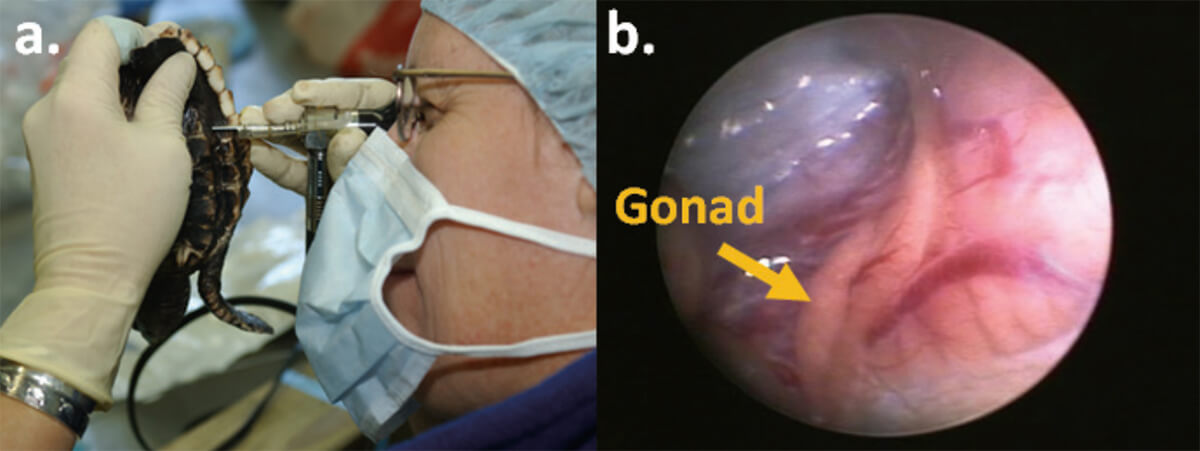

Currently, there are only two techniques that can be used to identify the sex of young turtles. One technique requires microscopic examination of their gonads (reproductive organs). This technique is very reliable but it has huge drawback; the turtle must be sacrificed which is the last thing we want to do when trying to protect an endangered species. The second technique requires “looking inside” with a small camera (or laparoscope) to see the immature testes and ovaries (Figure 3). This is a labor-intensive technique that allows for reliable identification of juvenile turtles without sacrificing the animal. However, it too has some important shortcomings.

Figure 3. Laparoscopic procedure to identify sex. (a) Dr. Jeanette Wyneken from FAU “peeks” inside at the reproductive organs of a ~four month old loggerhead turtle.

(b) Camera view of the gonad from a young loggerhead turtle.

(b) Camera view of the gonad from a young loggerhead turtle.

Hatchlings are too small for laparoscopic surgery so the turtles must be raised in captivity for at least three months, making the entire procedure a very expensive and labor-intensive method for determining sex and estimating nest sex ratios. Additionally, an expert must perform the surgery and make the identification. Those requirements make it impractical to obtain data on a large scale, for example, to determine how many males and females are being produced from the thousands of nests deposited each year on Florida’s beaches. What is needed, instead, is a simple and relatively inexpensive procedure for estimating nest sex ratios from hatchlings, without harming the turtles.

div This requirement motivated me and my collaborator, Dr .Itzel Sifuentes-Romero, to develop a new sex-identifying technique that could be used on hatchlings. The idea was simple: find a sex specific molecule that could be analyzed from a tiny drop of hatchling blood, so small that the turtle could immediately be released in the ocean, unharmed. The tricky part was knowing what molecule would fulfill that requirement. To find out, we had to search through past publications describing what little was known about the biochemical correlates of sex determination. As mentioned earlier, sea turtles don’t have sex chromosomes, meaning that males and females have the same set of genes (or instructions). So, the sex of the individual turtles is determined by which pages of the instruction manual are read, that is, which proteins are called into action. Fortunately, previous studies had revealed a number of potential protein candidates; our next task was to determine which of these could be detected in the blood, and which reliably indicated whether a male or female turtle was going to develop some 25 years later!

To make sure that we would have samples of both sexes, we incubated loggerhead sea turtle eggs at both male and female promoting temperatures. Immediately after the eggs hatched, we collected blood for analysis, then raised each turtle in the lab to later verify its sex via laparoscopy.

Blood samples were analyzed using an immunoassay technique (Figure 4) that measures the presence of a molecule of interest. In this case, it was one associated with a developing male or female, but not both. We searched for a number of the candidate sex specific proteins until finally hitting the “jackpot”: a protein only present in the blood samples taken from hatchlings that weeks later could be identified with 100% accuracy by laparoscopic exam as males; it was absent from female blood samples.

Our technique fulfills the major requirements for quickly, and inexpensively (~ $25 per hatchling vs. $300 to rear the turtle for laparoscopy), identifying the sex of the hatchlings. It is minimally invasive for the turtles, quick (analysis takes 2 days from start to finish), and perhaps most importantly it makes it very easy to distinguish males from females. In short, this technique provides an alternative to raising relatively few turtles in captivity; instead, large numbers of hatchlings from nests placed on many beaches can be quickly sampled on an annual basis. That information will enable managers to more precisely monitor changes in sex ratios that might arise from changes in climate over the years, and thus predict how those changes will affect future generations of the turtles. Armed with that information, managers can devise strategies to deal with the consequences now, before they become serious factors that threaten the recovery of marine turtle populations. This research was partially funded by The National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation.

Figure 4. Graphical representation of an Immonoassay. (a) Different shapes represent different proteins found in a blood sample. (b, c) After identifying a protein of interest (green cylinder), the sample can be treated with an antibody especially designed to attach to that protein. (d) If the protein is present in the sample, the antibody will bind to it. (e) The antibody-protein complex can then be stained and easily visualized from a blood sample. In this study, that complex was found only in blood samples taken from turtles that became males.

Helping Sea Turtles Survive for 39 Years

A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

State of Florida Registration Number CH-2841 | Internal Revenue Code 501 (c) (3)

Web Design & Development by Web Expressions, LLC