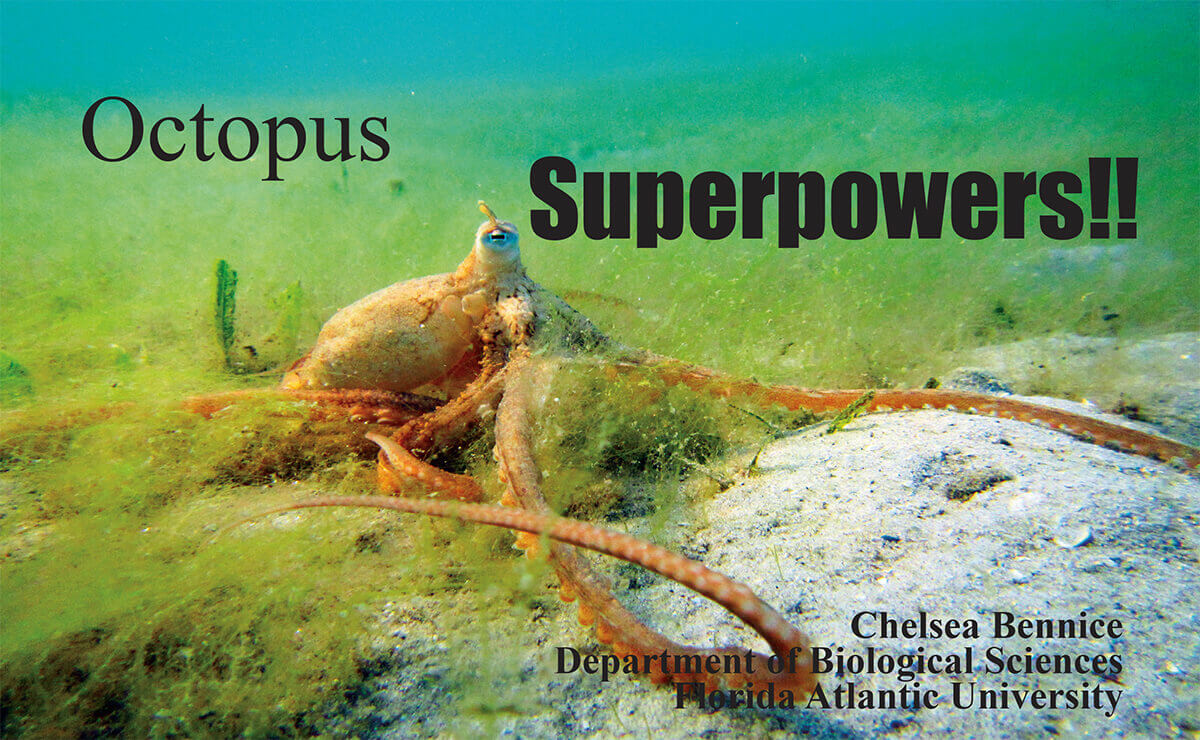

Octopus Superpowers

Fig. 1a: The Atlantic Longarm Octopus, Macrotritopus defilippi

I descend beneath the surface at Blue Heron Bridge in South Florida and watch as an Atlantic longarm octopus soars across the sandy bottom while hunting a crab.

Fig. 1b: The Common Octopus, Octopus vulgaris

As a graduate student at Florida Atlantic University, I am studying the superpowers of two octopus species, the common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) and the Atlantic longarm octopus (Macrotritopus defilippi; Figure 1). To fend off predators (fishes, marine reptiles, marine birds, and marine mammals), feed, and find mates, octopuses and their relatives, squids and cuttlefishes, are equipped with a large brain that allows complex body patterns and behaviors, thanks to millions of years of evolution (Figure 2).

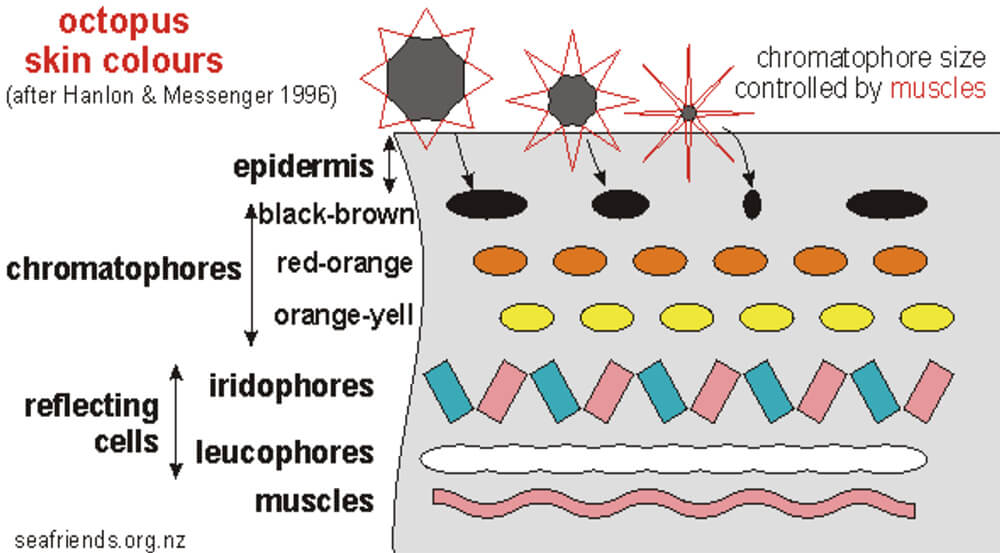

Most of us only think of the color changing organs (chromatophores) as being responsible for the octopus’s extraordinary color changing ability. However, these chromatophores act in conjunction with reflecting cells and other structures in the skin to produce a final appearance known as a body pattern. Color change is accomplished by these tiny color-filled sacs acting under direct control of the brain. Chromatophore patterns are controlled by the octopus’s eyes. This visual input travels to the brain, the brain selects a body pattern, and then this information is sent to muscles in the skin that are connected to these tiny color-filled sacs. Those sac muscles will either expand (display color) or contract (minimize color) the chromatophores (Figure 3). Chromatophores are either red, orange, yellow, brown, or black. To produce other colors, octopuses use reflecting cells known as iridophores, reflector cells, and leucophores that reflect blues, greens, silvers, pinks and white. By working under neuromuscular control, tens of hundreds to thousands of chromatophores are able to change an octopus’s body pattern in under a second!

Fig. 2: O. vulgaris being stalked by a diving cormorant

Fig. 2: O. vulgaris being stalked by a diving cormorantSkin texture is controlled by muscles in the skin that can change the skin from smooth to rugose to highly papillate (Figure 4). Skin texture and the appearance of the octopus’s arms, head, eyes, mantle, or arm webbing, as well as how the octopus moves, all contribute to the animal’s body pattern. Essentially, body patterns are used either for crypsis (resemblance to background) or for communication. The cryptic pattern may be uniform if the octopus is on sand, mottled if the octopus is on contrasting light and dark rubble, or a disruptive pattern that breaks up the outline of the body so the shape of the octopus is obscured. But camouflage doesn’t stop there! Octopuses can mimic other animals or resemble plants, algae, or rocks, a behavior known as masquerade and used to deceive either predators or prey. The ability to generate patterns and to change them instantly is a powerful combination. “Chameleons of the sea” is a weak description of these animals and their superpowers!

The octopus’s world is full of villains (its predators) and the octopus must be equipped to survive its foraging journeys (Superheros have got to eat, too!). Most octopuses are active predators, balancing their life by attacking prey and retreating back to the safety of their home (commonly referred to as a den). Octopuses have a well-developed brain and learn quickly; in fact many of their activities depend on previously learned individual experiences. Those activities include knowing their surroundings so they can return to their den after a foraging journey, and attacking potential prey with caution. With familiar objects, an octopus may pounce on its prey. With unfamiliar objects the octopus may be extremely cautious and extend its arm(s), touching the object with the arm tip before grasping and then drawing it underneath its web. Finally, it may make a beeline and land directly on the object. Octopuses have good image-forming eyes and most of them hunt their prey by sight. Yet they supplement vision with the use of chemotactile senses based in the suckers, which allows them to taste by touch! The main food items of the two species I am studying are clams, conch, and crabs (Figure 5A & B).

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of octopus skin: The epidermis (top skin) protects the underlying skin and is transparent. Directly underneath are three layers of chromatophores with colors depending on each octopus species. Each chromatophore is surrounded by a ring of muscles. These small muscles expand and contract tiny color-filled sacs (color cells) under control of the nervous system. Underneath the color cells are the different types of reflecting cells and under these cells is a layer of muscles that can change the texture of the skin.

Fig. 4: O. vulgaris changing skin texture. Notice the raised skin or skin papillae.

The two shallow-water octopuses I am study will use flounder mimicry (Figure 6), the moving rock trick (Figure 7), or flat camouflage (Figure 8) to avoid predators while searching for prey. Predators are not always avoided. When octopuses are detected by a potential predator they use their behavior and body patterns for deceptive communication and/or warning. Octopuses may flash dark spots as warning signals (“Back off, I see you”!) or will expand their web to appear much larger than they actually are (Figure 9).

Octopus superpowers ultimately aid their survival; however, these superpowers are not important unless they are passed on to the next generation. Octopuses are like rockstars- live fast and die young. Their lifespan is about 1-2 years, but it can be longer depending on species. Observations suggest that physical contact plays a role in species and sex recognition. Octopuses have been observed to mate in different ways. The common octopus, O. vulgaris, conducts mating at a distance using the “reach” method (Figure 10), or by the male mounting the female. Recent field observations showed that male M. defilippi mounted his female.

In many species of octopus, males compete aggressively for mating opportunities. Behavioral displays involve the use of enlarged webbing, showing arm suckers, or actual physical force (fighting). In those contests the larger male usually wins and ultimately drives off the smaller male (Figure 11). During mating, a male will place a packet of sperm in a modified arm (“hectocotylus”) that is inserted inside the female’s mantle cavity, where her reproductive organs are located. Once the eggs are fertilized, females will extrude the eggs, either individually or intertwined with other eggs in a cluster containing of many eggs. These are then attached to a hard substrate in a protected, den-like area. The female guards the eggs for several months, up to a quarter of her life span! Females only leave their eggs briefly to feed, and some never do. Females also keep the eggs clean and well aerated by moving fresh, oxygenated seawater over them until they hatch.

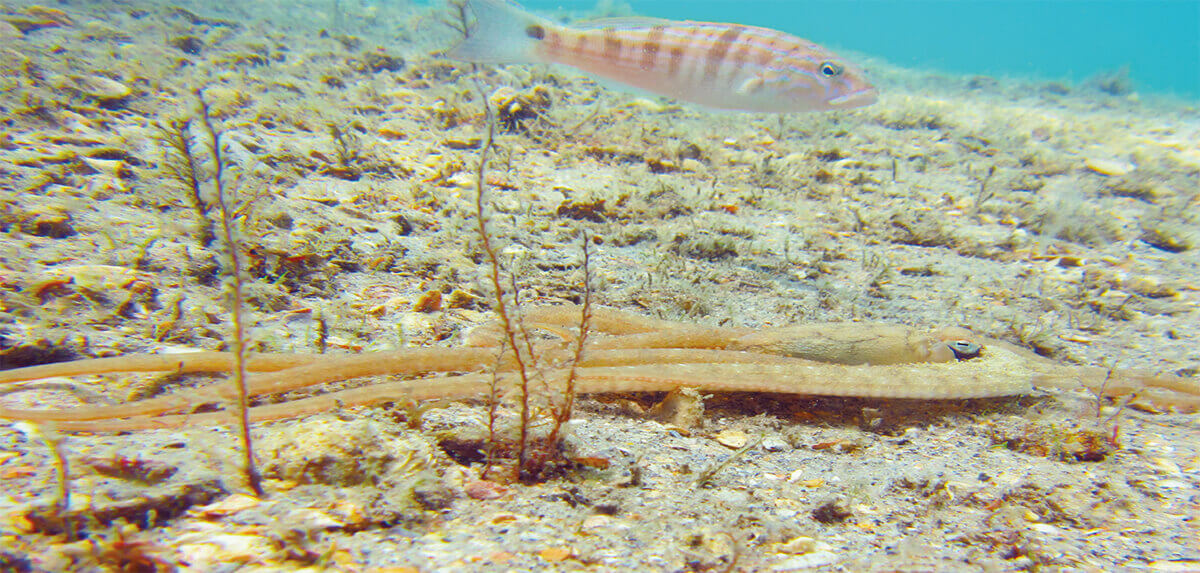

Figure 6. M. defilippi using flounder mimicry while foraging. A fish follows to catch any scraps of food left behind!

Figure 7. O. vulgaris using the moving rock trick (masquerade) to walk across the sand (images left to right).

Octopuses have these superpowers to survive in environments with predation and competition pressures. However, predation is a natural process where octopuses serve an important role in many marine food webs. They are a food source for animals higher in the food web such as fishes, diving birds, and marine mammals and serve as important grazers on animals lower in the food web such as clams, conch, and crab. Overall, this is crucial for a marine ecosystem’s community structure and biodiversity. Let’s do our part in conserving the marine environments (reefs, tide pools, seagrass beds, sandy plains, deep sea) that octopuses need for a habitat, food source, and reproduction to make sure these superheros live on.

Figure 8. M. defilippi using flat camouflage (general background resemblance) to match its surroundings. Arrow indicates the octopus’s head.

Figure 9. Octopus “reach” mating behavior. Male O. vulgaris (left) sitting on top of rock extending its hectocotylus (sex arm) inside the mantle of female O. vulgaris (right).

Helping Sea Turtles Survive for 39 Years

A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

State of Florida Registration Number CH-2841 | Internal Revenue Code 501 (c) (3)

Web Design & Development by Web Expressions, LLC