Leatherback Nesting in Southeast Florida

Kelly Martin, President

Florida Leatherbacks, Inc.

Florida Leatherbacks, Inc.

With the support of The National Save the Sea Turtle Foundation, biologists from Florida Leatherbacks Inc. were able to purchase a brand new ATV to allow them to continue their long-term research on Florida’s nesting leatherback sea turtles. With this ATV, they were also able to track two turtles with long-term satellite tags in addition to the routine population monitoring that they have conducted for many years.

Leatherback sea turtles are the largest living turtles and unique among sea turtles for many reasons. Feeding on a diet of jellyfish and other soft-bodied marine animals, leatherbacks can reach lengths of 2-3 meters and weigh up to 700 kgs. Leatherbacks are named for their rubbery skin and their carapace is composed of thousands of tiny bone plates and a thick fat layer. This flexible structure allows their body to expand and contract with water pressure, enabling them to dive to depths of over 1,000 meters. Leatherbacks also have unique adaptations that allow them to tolerate much colder water temperatures than other marine turtle species.

In the Atlantic Ocean, major nesting beaches exist in Gabon, Trinidad, Suriname, Guyana, and French Guiana. Most of these beaches have seen increases in nest numbers over the last several decades. In stark contrast, leatherback populations in the Pacific Ocean have declined by more than 80% in recent years. Major nesting beaches in the Pacific include Indonesia and Papua in the western Pacific, and Mexico, Panama, and Costa Rica in the eastern Pacific. It is not known what has caused such sharp declines in the Pacific though poaching and fisheries interactions are thought to be leading factors.

Florida, despite being one of the densest loggerhead sea turtle nesting beaches in the World, hosted very little leatherback nesting in the mid-1900s. However, since 1979, the number of leatherback nests in Florida has been increasing by approximately 10% per year. Due to the lack of appropriate data regarding leatherback survival rate, remigration interval, internesting interval, and population size,

FIU Research Team collecting samples. Photo credit: CASE News

very little was known about this new and growing population, including why they had not been previously documented in large numbers in Florida. One key way to address these deficiencies is by creating a long-term, mark-recapture program designed to use tags to identify unique individuals within a population and monitor their return over the years.

Leatherback tagging began on some Florida beaches as early as the 1980s. Biologists currently working for Florida Leatherbacks Inc. (FLI) began tagging leatherbacks on some of the more densely nested beaches in southern Florida in the early 2000s. In addition to tagging each individual, a tissue sample was taken for genetic analysis and the turtle was measured and checked for any injuries. The mark-recapture data from these studies have been used to define survival rate, remigration interval, population size, clutch frequency, genetic structure, and many other important biological parameters. Incorporating the use of satellite transmitters helped define important migratory routes and post-nesting movements of Atlantic leatherbacks.

Despite many years of successful data collection, researchers noted that some individuals were observed only once in a nesting season while others laid as many as eight nests. There were also widely ranging remigration intervals, often as high as ten years, despite a presumed remigration interval of 2-3 years. One proposed reason was the low site fidelity of leatherbacks. Researchers suspected that turtles tagged on their study area were also utilizing beaches throughout the southeast coast. This was supported by the incidental captures on adjacent nesting beaches during morning nesting surveys. Low site fidelity makes it difficult to get a true estimate of nesting parameters by surveying just one small area. Estimated clutch frequency and population size become skewed because the probability of recapturing them declines as nesting range increases. In 2014, biologists with FLI expanded upon their work that began at Palm Beach County by including the beaches of Martin County, which host the highest density of leatherback nesting in the state.

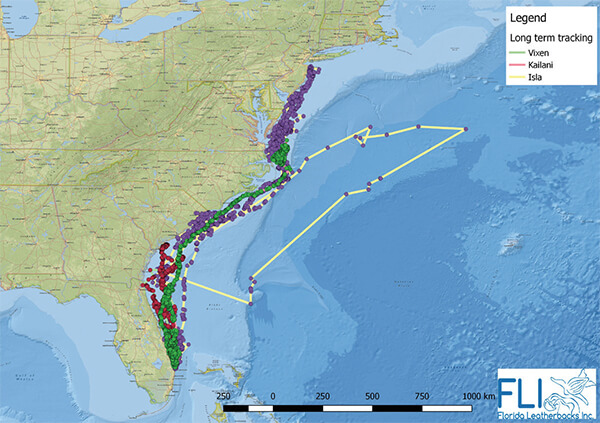

During 9-11 day nesting intervals, the majority of leatherbacks leave the beach and head east to the Florida Current. They quickly move north and stop near Cape Canaveral, remain there for 2-3 days, and then slowly move back south to nest again.

Leatherbacks observed during this study have also been observed to have international ties. One turtle tagged on a Florida beach was caught by the Canadian Sea Turtle Network in the waters off Nova Scotia as part of their ongoing inwater research. In 2014, a turtle emerged to nest on Jupiter Island with tags that had been applied while she was nesting in Costa Rica in 2001. This confirms what genetic analysis has preliminarily shown. Initial results indicate genetic similarities between turtles that nest in Florida and those that nest in St. Croix, Trinidad, and Costa Rica. It is very possible that the turtles that colonized Florida nesting beaches originated in one of these larger nesting grounds.

Satellite data and dive profiles from turtles outfitted with transmitters have provided valuable information about leatherback behavior during the nesting season as well as after they leave for the year. Leatherbacks nest every 9-11 days and the majority leave the beach after a nest and head east to the Florida Current. They quickly move north utilizing this current system and stop near Cape Canaveral where they turn west, remain there for 2-3 days, and then slowly move back south to nest again. After their last nest of the season, they travel north along the eastern US coast and often end up in the waters off New York, New Jersey, and even as far as eastern Canada where they feed on large jellyfish aggregations. When northern waters begin to cool in the fall, they will migrate to foraging grounds in the mid or southern Atlantic and continue this pattern until returning to Florida to nest again. Leatherbacks are capable of diving more than 1,000 meters but spend a large amount of time at the surface, typically surfacing to breathe every 5-10 minutes.

Surveys of Jupiter Island began in 2014 and expanded to include Hutchinson Island in 2016, incorporating a total of 32 km of beach. During the leatherback season that spans from March through June, biologists with FLI survey the beaches in search of nesting leatherbacks. Each leatherback encountered is first checked for tags. Since tagging has taken place for over 20 years in Florida, many turtles have tags from previous years. Tags are checked for integrity and turtles are examined for signs of undocumented injuries. Untagged turtles receive two metal flipper tags and a PIT tag. They are measured and a skin biopsy is collected. Each nesting season, 1-3 turtles are also outfitted with a satellite transmitter to look at movement, dive behavior, and post-nesting migration.

Between March 2014 and June 2019, FLI biologists encountered leatherbacks a total of 1,716 times. These encounters were with 496 individual turtles who were observed between one and eighteen times each. 211 of these turtles were untagged. The remaining 286 turtles were tagged prior to 2014 in either Palm Beach or Brevard County. 148 turtles were seen on only one occasion throughout the four-year period, confirming suspicions that leatherbacks likely have very low site fidelity. While it is possible that these turtles were nesting only a single time during the season, there were multiple turtles that were observed nesting eight to nine times within a single season. In 2018, one turtle laid 11 nests, the first time this was documented. Turtles were often observed nesting in both Palm Beach and Martin Counties throughout the season.

The Florida Leatherbacks Team readies for another night-long survey.

In 2018, FLI began a partnership with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in Canada to track nesting turtles long-term with a new method of directly attaching a transmitter to a turtle’s dorsal ridge. This study was designed to look at the movements of turtles from Florida nesting beaches to Canadian foraging grounds. In 2018, a leatherback named Isla was tagged on May 11th. Isla laid a total of 11 nests during the nesting season, the first time this has been documented. This would not have been possible to determine without satellite data since she nested on various beaches throughout the east coast. Isla is still transmitting off the coast of Maryland and has traveled over 22,950 km (14,260 miles), providing us with valuable data about the foraging grounds she has used.

In 2019, two long-term transmitters were applied. Kailani was tagged on March 25th and laid at least 9 nests before leaving. She has traveled over 9,850 km (6,120 miles). She is currently in almost the same spot as Isla off the coast of Maryland. Vixen was tagged at the end of the nesting season on June 15th and has traveled over 3,470 km (2,156 miles). She is currently off the coast of South Carolina. You can follow all tracked turtles at www.trackturtles.com.

Long-term population studies are often the only way to answer many questions about life history, reproductive biology, and habitat use, particularly for long-lived and wide-ranging animals. It is important to continue to use individual identification over a multi-decadal time frame to better understand this population and the potential impacts of anthropogenic forces on its survival. Data collected from this study are used by governmental and management agencies to better understand this extremely important nesting aggregation and create recover strategies best tailored to this population. The support of the National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation this year made all of this possible.

Helping Sea Turtles Survive for 39 Years

A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

State of Florida Registration Number CH-2841 | Internal Revenue Code 501 (c) (3)

Web Design & Development by Web Expressions, LLC