The Pluses and Minuses of Using AMDRO© to Protect Marine Turtle Nests from Fire Ants

Heather Smith

Biological Sciences

Florida Atlantic University

Biological Sciences

Florida Atlantic University

When most people think of sea turtle predators, fire ants are probably not the first creature that comes to mind. Aside from being an unwelcome addition to backyard fauna, fire ants can wreak havoc on sea turtle nests and hatchlings. They can prey on unhatched eggs, and they’ve even been known to excavate tunnels used to monitor nests for the emergence of hatchlings. Even worse, a single ant sting suffered while escaping from the nest can kill a hatchling sea turtle, even after it successfully crawls to the ocean.

Currently, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which administers permits to both monitor and study marine turtles in our state, recommends removing fire ant mounds located near sea turtle nests by using a shovel and bucket, or by pouring boiling water onto the mounds. While these methods can work in some cases, they’re impractical at many nesting beaches. A more efficient method for removing the threat posed by fire ants would probably be welcomed by nesting beach managers and personnel - a method that is both physically easier and more practical on remote nesting beaches.

Such an alternative at nesting beaches might be the use of the granular bait pesticide known as Amdro©, which is widely used for the control of fire ants on residential lawns. This pesticide is generally considered to be both effective and relatively harmless to the environment. It is not very water soluble, so it is unlikely to dissolve in rainwater and contaminate the area.

Figure 1. Left, loggerhead hatchlings emerge from their nest. Right, tracks left on the beach the morning after an emergence show that after leaving the nest (located underneath the white circle), the hatchlings crawl directly to the surf zone.

Figure 2. The author is shown here sprinkling Amdro© granules on top of a loggerhead nest.

We had multiple sets of control nests exposed to harmless corn grit granules or no treatment at all, and multiple sets of experimental nests that were exposed to Amdro©. After the hatchlings had left those nests, we excavated them and compared the emergence success shown by the two nest categories (Figure 3). This is a physically demanding and sometimes smelly, but relatively straightforward, task. To summarize, I found that emergence success was uniformly high and equal between the two nest categories. So, Amdro had no apparent effect on turtle embryonic development or hatchling vigor, as measured by the turtles’ ability to complete development and leave the nest.

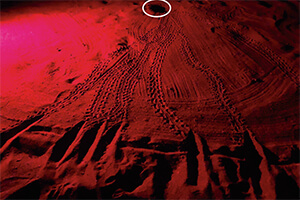

But how do you determine if a hatchling sea turtle is visually impaired? Fortunately, I was able to take advantage of the instinctive behavior of hatchling sea turtles. I captured them immediately after they emerged from their nest and briefly interned them inside small, sand-filled coolers while they were taken a short distance down the beach to another location. At that site, we drew a big circle in the sand, used a broom to sweep the sand smooth, and created a shallow depression in the center of the circle (called an “arena”). Then I placed the turtles in small groups in the center of the depression and let them crawl out, mimicking a second “emergence”. We used their flipper tracks, left on the smoothed sand surface, to determine their crawl direction (Figure 4). At Juno Beach, this angle should be east (~ 90◦), the direction that takes the turtles most directly from their nest to the water.

Managing a protected species requires a constant cost-benefit analysis with regard to the best methods for recovery, and with every action there is often a cascade of unforeseen effects. We are lucky to have a wide array of tools available to us to aid in our conservation efforts, but it is important to continually verify that the tools we are using are having their intended effects. This is the crossroads where research and conservation must meet, so that wildlife managers can make more informed decisions with regard to their management practices. This research was partially funded by The National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation.

It also degrades quickly in sunlight and is therefore unlikely to persist long enough to be a long-term problem for wildlife. All of this being said, it is still a pesticide that is known to cause reproductive problems, dermal abrasions, and visual impairment in other vertebrate species. For these reasons, I collaborated with researchers from the Loggerhead Marinelife Center and Florida Atlantic University to carry out a series of experiments designed to determine if this pesticide, when used to protect sea turtle nests, was causing any harm to the hatchlings it was intended to protect.

The red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Photo: S. Porter, USDA.

My study had two primary goals. First, I wanted to know if Amdro© had a negative effect on embryonic development, as measured by the proportion of the eggs that resulted in hatchlings that exited the nest and presumably crawled to the sea. This observation is known as the nest’s “emergence success” (Figure 1, left). Second, I wanted to know if contact with this pesticide could result in hatchling visual impairment. Hatchlings depend upon eyesight to determine at night (when they typically emerge) which direction will lead them from the nest to the sea, a behavioral process known as “seafinding” (Figure 1, right). To answer these questions, I applied a small quantity of the pesticide to the sand directly on top of loggerhead sea turtle nests up to 10 days in advance of an anticipated emergence (Figure 2). The Amdro© granules are bright yellow and attracted some attention from beachgoers! Many asked, “Is that food for the turtles?!”

It is hard to explain why you would want to purposely place a pesticide on a nesting beach. In this case, the benefits could outweigh the costs if, by doing so, nests are protected from the ants. But what are the costs? Luckily, emergence success is a relatively easy thing to determine.

Once again, we compared the performance of hatchlings from control and Amdro©-treated nests, and once again there were no differences. The turtles from both groups crawled to the east. This told me that Amdro had no apparent effect on the ability of the turtles to visually locate the sea.

Generally speaking, if you peruse marine turtle toxicology papers, you will rarely find good news. The effect of other pesticides on sea turtles is almost always negative, leading to reductions in fertility, tumors, and drastic impacts on body condition. Fortunately, this study produced different results. I did not see evidence for an effect of Amdro. However, I did notice something potentially concerning. As we were monitoring nests for the emergence of hatchlings, we noticed that nests exposed to Amdro© tended to attract the interest of more predators than control nests.

Figure 3. Excavating a sea turtle nest to determine emergence success. It’s a smelly job

but one that’s required to determine how many turtles left the nest.

but one that’s required to determine how many turtles left the nest.

The most common predator was the Atlantic ghost crab which can prey on sea turtle eggs and hatchlings. The smell of the cornmeal and soybean oil carrier in Amdro© could be a ghost crab attractant, potentially drawing predators to the nest site. In my study, the added predators did not translate into a noticeable reduction in nest productivity, but at the same time, that effect could prove to be damaging at other nesting beaches. Amdro© exerts it influence on fire ants by attracting the ants, inducing them to take the insecticide back to the nest, and by poisoning and eventually killing the ant queen. Attracting other predators to nest sites that are otherwise difficult to locate might be a cost that has to be considered before using this pesticide at other nesting beaches.

Figure 4. This photo shows the tracks of several

hatchlings that crawled from a depression in

the center of the arena (white circle) toward

the arena boundary. Note that all of the

tracks are oriented in about the same (seaward) direction.

hatchlings that crawled from a depression in

the center of the arena (white circle) toward

the arena boundary. Note that all of the

tracks are oriented in about the same (seaward) direction.

Helping Sea Turtles Survive for 39 Years

A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

State of Florida Registration Number CH-2841 | Internal Revenue Code 501 (c) (3)

Web Design & Development by Web Expressions, LLC